Favourites from the Folk Life Collections at the Manx Museum

The Manx Museum may be closed during the Coronavirus lockdown, but it’s still possible to discover more about some of the objects in the National Collections and the fascinating stories behind the objects themselves and the people who made and used them in the past.

Here are a selection of some of the objects from our folk life collections which have captured the interest and imagination of Curator of Social History, Yvonne Cresswell:

Boat Models: Tales of a Life and World at Sea, Captured in Miniature

One Man’s Tale of Returning to his ‘old love’ – a model of the Zetetic CT 35

In 1939, John Duke of Foxdale made a model of the fishing boat Zetetic for the Manx Museum. The model was more than just a beautifully made and detailed record of what the Zetetic (and other 19th century Manx fishing boats) looked like, it was also an important part of his own family history and life. The Zetetic was built in St Ives, Cornwall in 1876 and was one of several west Cornish ‘luggers’ (fishing boats) in the Manx fishing fleet, where they were known as ‘Nickeys’. The vessel was registered at Castletown as CT (Castletown) 35 and John Duke’s father, Richard Duke, was her skipper and more importantly he was Admiral of the Manx Fishing Fleet so the Zetetic, had the honour of the carrying the Commodore flag of the Manx fishing fleet.

- Discover more about Manx fishing and fishing boats.

- Discover more about the Admiral of the Manx Fishing Fleet.

- Can you find Zetetic CT 35 in any of the photographs or artwork on the iMuseum? If you can, we’d love to know. Two of the Zetetic’s Cornish-built ‘sisters’ (CT 9 Cedar and CT 10 Zebra) can be seen in this picture of Port St Mary inner harbour.

During a long and varied working career (and having left school at a young age), John Duke first ‘went to the fishing’ at Kinsale, Ireland but returned to the Island to farm at Ballaoates. It wasn’t long though before he returned again to the fishing and began working in the Hebrides (even landing on St Kilda). After that he was working on the docks in Liverpool, followed by time as a police officer before finally returning to the Island in 1915. Supposedly retired, John Duke was tenant farmer for 10 years until finally retiring in 1925. After a few more house moves, he settled in Foxdale and returned to his first love of fishing – not at sea but in a shed in his garden where he made this fishing boat model for the Manx Museum.

- Discover more about John Duke’s Golden Wedding Anniversary celebrations in the Manx newspapers on iMuseum (Isle of Man Examiner, Friday, June 23, 1939).

So what does Zetetic actually mean? It means proceeding from enquiry from the original Greek to seek. In the 19th century, people would have heard it in relation to Zetetic astronomy (a variation on the ‘flat earth’ theory). The Cornish ‘nickey’ wasn’t the only Zetetic in the Manx fishing fleet, as a second later fishing boat (sailing from Peel) carried the same name until the 1930s. Why two fishing boats were called the Zetetic it’s difficult to say. It may have been an interesting sounding name and a more exotic sounding variation on the more traditional name ‘Seeker’ for a fishing boat.

Hands of a Giant: Tales of Mystery and Intrigue

Who was the Manx Giant?

The life-size bronze casts of Arthur Caley’s hands.

Arthur Caley, the so-called Manx Giant, was born at Sulby in 1824. A popular myth has it that the doorways of the Sulby Glen Hotel were raised in order for him to pass through, but in fact the hotel post-dates Caley by some years! He was a true giant in the sense that his limbs were in proportion to his body, and he is reported to have reached a height of 7 foot 8 inches. He soon attracted attention because of his height, and found work in a circus where he would often appear alongside dwarves, in order to further emphasise his height.

It was falsely reported that he died in Paris in 1853, and this may have been some sort of fraud on the part of his manager, because Caley later appeared in the United States under the pseudonym of Colonel Routh Goshen, the Palestine Giant. He joined a circus there under the management of the celebrated impresario P.T. Barnum, and toured the country. He died in 1889, and is buried in Middlebush, New Jersey, where his gravestone bears the inscription ‘Middlebush Giant’.

Life-size copies of Arthur Caley’s right hand (the Sulby Giant) were cast in solid metal (a bronze/ copper alloy) and are extremely heavy. The detailed casting shows the hand with slightly bent fingers together with details of the finger nails and joints. The cast of the hand was probably made to cash in on Caley’s fame, or to publicise the circus, and several examples are known to exist. They are now highly sought after by collectors of circus or ‘freakshow’ memorabilia.

An unusual variation of the life-size metal hand is one that has been made into a container, possibly a snuff box. The hand has a metal hoop attached to the wrist and an engraved silver plaque fastened to the back of the hand. The hinged plaque can be lifted up to expose a smaller box compartment in the centre of the hand (a snuff holder/ box). The inscription on the silver plaque reads ‘A, Model, of, the, late, Arthur, Kaley’s, hand. The.Manx(s).Giant, stood, 7ft 8in aged, 22, years. This particular cast of his hand (or at least the inscription on the plaque referring to him as the ‘late Arthur C/Kaley’) appears to have been produced after his supposed death in Paris in 1853.

The hand with the silver plaque was originally part of the ‘Penny Arcade/ Circus/ Carnival’ collection of James W. Smith Jr. (Surgeon/ 1926-2006) and was donated to MNH by his widow, Mrs Nancy K. Smith.

- Interested in seeing what Arthur Caley looked like? Photographs of him as ‘Colonel Routh Goshen’ are on the iMuseum.

- Discover more about Arthur Caley in the iMuseum newspapers.

- The giant’s hands can also be see on gateposts in Regaby.

- Want to discover more about something even curious than the hands of a Manx Giant? Have a look at the tiny metal cast hand found in a cod!

Rushlight and Candle Holder: Bringing Light in the Darkness

How did people light a building before gas and electric lighting?

A rushlight & candle holder from St John’s church.

Before the advent of electric or gas lighting or even oil lamps, many people would have lit their homes with candles or the more basic rushlights. Beewax candles would have been too expensive for anyone but the wealthiest to use (although they did smell a lot better than tallow candles). Even tallow candles, which were made from animal fat (and didn’t smell very good) were probably too expensive for many people to use on a daily basis. As a result the humble rushlight would probably have been found in most cottages, if light (other than from the turf fire) was required.

So what is a rushlight? A rushlight is a very simple, basic and cheap type of ‘candle’ where a length of dried rush (the pith inside the stem) is dipped/ soaked in animal fat. These could be made easily at home using rushes from the surrounding fields and fat/ grease left over from cooking. The rushlight holder itself would be made by the local blacksmith and would be made up of two pieces of hinged metal that clamped together to hold the rushlight whilst it burnt. Rushlight holders were often combined with a metal candle holder to hold a home-made tallow (animal fat) candle, useful if someone wanted more light and for longer than that provided by a simple rushlight – a very simple but effective lighting system for the home.

Manx National Heritage has a variety of different types of rushlight and candle holders in its collections, which would have been used in a variety of different cottages and farmhouses around the Island during the 18th and 19th centuries, but this particular rushlight and candle holder is unusual because it was said to have been used in a church to provide light.

The rushlight holder originally came from the Duke family of St Johns and Mrs Duke had said that it had come from the old church at St Johns before it was demolished in 1847, to make way for the new church you see today and which was built 1847-1849.

Tynwald Hill (with chapel in background) by George William Carrington, 1820. Accession number 2009-0009a.

The wrought iron rushlight & candle holder has a cruciform (cross-shaped) wooden base, probably to make it more stable and less likely to be knocked over. It was probably made by a local blacksmith and may have been one of several used in the chapel, possibly together with oil lamps, to provide light during services and the meetings of the Tynwald Court held at the chapel.

The rushlight and candle holder was purchased by the Manx Museum in the 1930s for the Museum collections for 4/6 (about £12 today) and the Manx term recorded for it was a Cainlere (the word used in Manx Bible for candlestick).

- To discover more about ‘The Light of Other Days’, read I.M.Killip’s account from the Manx Folk Life Survey of how people lit their homes in the past (and how to make rushlights).

- Read about how quickly lighting changed through a lifetime, in this 1934 newspaper article about new electric lighting at Foxdale Chapel.

Sun Dial: Measuring Time With the Passing of the Sun

How to tell the time and how time has become more important: copper and slate sundials

Being able to accurately tell the time is a fairly recent innovation and the need to be able to accurately tell the time and know what the time was has only been important for less than 200 years. For millennia, people’s lives and working patterns had been driven by the hours of daylight and the rising and setting of the sun. Later, people’s lives might be governed by the ringing of bells, in particular the church bell toiling before the start of a service. But by the mid to late 19th century everyone needed to know the time and public clocks could be seen at railway stations, schools, factories, churches and market places – everyone had somewhere they needed to be and they needed to be there on time. Time was no longer based on local time and governed by the sun, instead Britain had a single ‘Railway Time’ governed by railway timetables which eventually became the Greenwich Mean Time (GMT) we know today (and Bristol is no longer 10 minutes behind London).

But before time became so important and when only the very wealthy owned clocks, there was a way to measure time and this was with a sundial. They were often found in the grounds and gardens of large houses and on farmhouse walls or in churchyards and on the walls of churches.

How does a sundial work? A sundial is a dial – flat plate marked with radiating numbered lines that represent each hour of the day and a gnomon – a triangular plate set at right angles on the dial and which casts a shadow onto the dial. The length of the shadows cast by the sun changes during the day and move across the radiating lines so that the viewer can tell the (approximate) time of day – but only if it’s sunny. Sundials can be placed either horizontally on top of a column or vertically on a wall.

Manx National Heritage has several examples in its collections including:

A small square Copper Sundial with the inscription ‘this dial left by George Barns of Douglas, 1708 to Kirk Conchan Church’. A George Barnes is listed in the Onchan Church register as having been buried on the 23rd June 1708, so he may have left money in his will for the sundial to be erected in his memory. The Onchan church that George Barnes would have known was relatively small and was in an increasingly poor state of repair by the late 1700s, although it wasn’t demolished until 1830 and replaced by the new and larger church we know today until 1833.

The sundial was presented by Mr C. Swinnerton to the Manx Museum & Ancient Monument Trustees in 1906, when the ‘Manx Museum’ was still located in Castle Rushen. The collection was moved in 1922 to its new permanent home in the old Nobles Hospital building and the sundial was accessioned as the 327th object in the new collections – hence it’s accession number of 1954-0327, one of the first objects accessioned into the permanent collections in 1922.

- Discover what the original Onchan Church looked like

A square Slate Sundial with the inscription ‘C. Howland Mathematic 1823’ and a copper gnomon. The sundial was presented by Dr Claude Shaw to the Manx Museum & Ancient Monument Trustees in 1910 and was said to have come from Lonan. When the museum collection was moved in 1922 to its new permanent home in the old Nobles Hospital building, the sundial was accessioned as the 694th object in the new collections – hence it’s accession number of 1954-0694, one of the first objects accessioned into the permanent collections in 1922.

Unfortunately there are no obvious candidates as to who C.Howland might be, why the date 1823 might have been significant or what the meaning and significance of the term ‘mathematic’ is in the inscription – do you have any ideas?

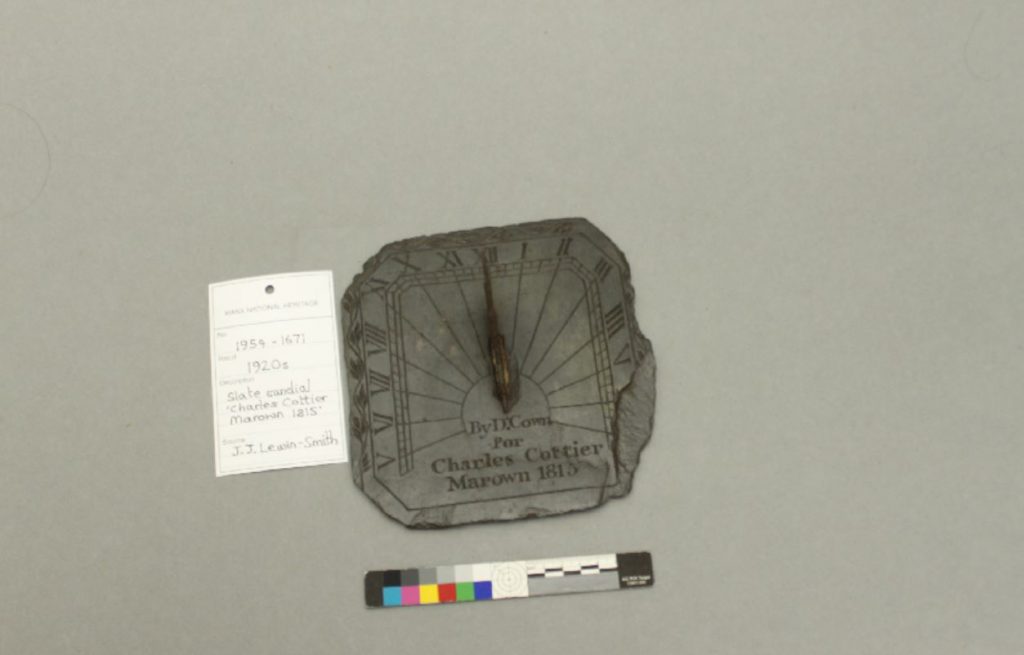

An octagonal Slate Sundial with brass gnomen and the inscription ‘By D.Cown for Charles Cottier Marown 1815’. It was donated to the newly opened Manx Museum in 1924-5 by J.J.Lewin (blacksmith) of Glen Vine, Crosby.

Unfortunately there are no obvious candidates as to who Charles Cottier might be, why the date 1815 might have been significant (other than being the end of the Napoleonic Wars) or where the sundial may have been in the parish of Marown – do you have any ideas?

- If you want to find out more about sundials, there were several articles written for the Proceedings of the Isle of Man Natural History & Antiquarian Society.

Hand Loom: Weaving the Cloth of Daily Life

A Home-Spun Life – James Creer of Colby’s Hand Loom

Until relatively recently and the advent of mass-produced clothing, most people wore clothes they had either made themselves or that a local dressmaker or tailor had made for them. Up until the 19th century, many people in rural communities would be wearing woollen cloth that had been woven in their own village by the local weaver, using wool that a person might have spun themselves from their own sheep. Although there were a few larger woollen mills on the Island, such as Moore’s Mills (now Tynwald Mills) near St Johns, most villages had their own local weavers. Even a village as small as Cregneash, once had 5 weavers working in the village – each with their own handloom (or Cogee in Manx) in the loom shed attached to the cottage.

James Creer of Colby’s wooden handloom was purchased by the Manx Museum & Ancient Monuments Trustees in 1906 and the Trustees’ Report for 1906 says:

- 27. HAND-LOOM (Cogee),date unknown, but considerably over a century old, worked by the late James Creer of Colby, until his death a couple of years ago, and purchased from his widow. Creer, with his own hand, added several modern labour-saving accessories, such as the flying shuttle, and loose pawl arrangements for turning both beams, but all the original parts of the loom still remain, and it can be worked as originally. Dimensions : height of frame 6 ft. 7 in., length, back to front 4 ft. 10 ins., breadth 5 ft. 4 in., loagane(feeler of tension) 10 ft. 2 in., garmin mooar as garmin beg (great and little beams), each 5 ft., darragh cleeau (breastbeam), 5 ft.

Parts of Loom and Accessories : Cogee loom ; soieag feddyr , weaver’s seat ; cadjalyn, treadles ; kiljyn, frame for laying warps before placing on garmin ; sling, reeds; spaal, shuttle ; greie, gear ; queeyl, wheel; cuillyn, reeds ; coir ny kiljyn, box for balls of warp ; ollan snaie, woollen thread ; gloo or jelliu, warp ; innagh, woof or weft; eggey, web ; queigyn, loose ends of warp ; slat, lath to which queigyn are attached to garmin ; fain a ghyn, rings for keeping lath in its place on the beams ; pash mooyn gort, vessel for ammoniacal urine, &c. The Manx terms here employed were taken down by Dr. Clague from the owner of the loom some years ago, and have been verified by reference to the Dictionaries of Kelly and Cregeen. A web has been placed in the loom by two weavers of experience from Kirk Arbory, and several yards have been woven.—By purchase.

The handloom was an important addition to the Manx Museum’s early collections for various reasons – it was one of the last handlooms to have been used on the Island, having been used by James Creer until his death (in 1904 – aged 74), it was warped ready for weaving and Dr Clague had already recorded (and then checked) all the Manx words and terminology for the loom and all of its constituent parts used by the weaver, James Creer.

Already old when the Manx Museum purchased it, the loom may have belonged to James Creer’s father, Richard Creer (1790-1866) who was also a weaver and even possibly to his grandfather, John Creer (1767-1834) as well. James Creer (1830-1904) was not just a well-respected weaver but he was also a wheelwright as well, who made and repaired spinning wheels and during his working life had made several ‘modern labour-saving’ devices and additions to his loom.

A Great Wheel

A Great Wheel (or a ‘Walking Wheel’) is an early type of spinning wheel, where the spinner stands at the side of the wheel and turns/ spins the wheel by hand and walks back to draw out the thread and then walks back to the wheel as the twist ‘travels’ up the thread. Later spinning wheels were smaller and where the wheel was turned by the spinner sitting at the wheel using a foot-powered treadle.

The ‘Great Wheel’ was owned and used by James Creer (1830-1904), weaver of Colby. The wheel may also have been made by James Creer (1830-1904), who as well as being a weaver was also a wheelwright who made and repaired spinning wheels. William Cubbon (2nd Director of the Manx Museum) in his book ‘Island Heritage’ says besides being a first-class weaver, James was a worker in wood, and the writer remembers that as far back as 1875 he carried his mother’s spinning-wheel to him in order to have some new spokes put in…

- See a photograph of James (Jemmy) Creer here.

- Discover more about James Creer and other Manx weavers in the Manx newspapers.

- Find out more about Manx weaving with I.M.Killip’s article ‘Keeir-Lheeah and Wullee-Wus: Some Notes on Manx Homespun’ from the Manx Folk Life Survey.

- Discover more about Alfred Hudson of Ballafesson and his hand-loom (now on display at Cregneash).

- See a traditional Manx skirt made of handwoven woollen fabric (possibly woven by Alfred Hudson).

- See a traditional Manx patchwork quilt made of handwoven woollen fabric (possibly woven by Alfred Hudson).

Yvonne M. Cresswell (MNH Curator of Social History)

Blog Archive

- Edward VII’s Coronation Day in the Isle of Man (9 August 1902)

- Victoria’s Coronation Day in the Isle of Man (28 June 1838)

- Second World War Internment Museum Collections

- First World War Internment Museum Collections

- Rushen Camp: Second World War Internment on the Isle of Man

- Hutchinson, Onchan & Peveril Camps: Second World War Internment on the Isle of Man

- Douglas Promenade: Second World War Internment on the Isle of Man

- Mooragh Camp: Second World War Internment on the Isle of Man

- Sculpture collection newly released to iMuseum

- Fishing Folklore: how to stay safe & how to be lucky at sea

- News from the gaol registers project: remembering the men and women who served time in Castle Rushen

- Explore Mann at War: stories of Manx men, women and children in conflict

- We Will Remember Them: Isle of Man Great War Roll of Honour (1914-1918)

- Dr Dave Burnett explores Manx National Heritage geology collection

- Unlocking stories from the Archives: The Transvaal Manx Association

- Login to newspapers online: step-by-step guidance

- ‘Round Mounds’ Investigation Reveals Rare Bronze Age Object